Sure! Here’s the translation to American English:

—

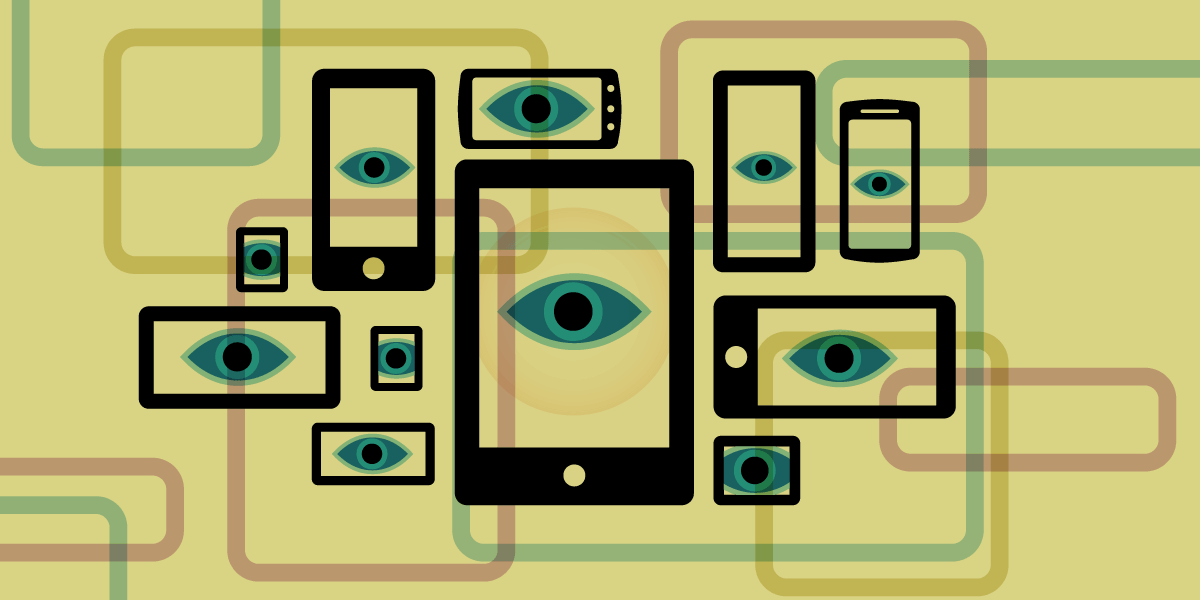

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which covers California and much of the western United States, has made a significant ruling regarding digital privacy. In a decision related to the case United States v. Hunt, the court determined that abandoning a phone does not mean giving up the rights granted by the Fourth Amendment concerning the content of that device.

The court clarified that losing control over a device does not entail relinquishing the privacy of the information it stores. According to the ruling, courts must separately assess whether a person actually intended to dispose of the phone and, furthermore, whether they wished to waive the data stored on it. This stance brings with it the certainty that, given the amount of personal information contained in our phones, it is unlikely that someone genuinely attempted to waive their privacy rights.

This approach aligns with the recommendations from the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), which participated in the case as an amicus, along with other organizations like the ACLU. It was argued that a person can separate from a device while still having a legitimate interest in the information it houses. Treating phones as mere forgotten objects ignores the current technological reality; these devices have become repositories of our daily lives, containing everything from messages and photos to location histories and health data. As recognized in the case Riley v. California, our phones represent “the privacies of life,” and accessing their digital content generally requires a search warrant.

The facts of Hunt underscore the importance of the distinction between a device and its content. In 2017, Dontae Hunt was shot and dropped his iPhone while seeking help. The police recovered the phone at the scene and retained it as evidence. Nearly three years later, during a drug-related investigation, federal agents obtained a warrant to review the content of the device. Hunt objected to both the seizure of the phone without a warrant and the subsequent search, arguing that he never waived either the device or its data.

The court dismissed the abandonment theory put forth by the government and established a fundamental line for the digital age: even if the police have legitimate possession of the hardware, they cannot access its content without judicial authorization. Additionally, it emphasized the need to treat the device and the data separately in the Fourth Amendment analysis.

While in this case the government obtained a search warrant before reviewing the device, the court deemed that the police acted reasonably in seizing the phone during the investigation of the shooting and keeping it until a warrant could be obtained to examine it.

The Hunt decision establishes that if authorities find a phone that has been lost, left in an emergency, or separated from its owner, they cannot assume they have unrestricted access to its entire digital content. This ruling ensures that constitutional protections do not vanish merely because someone abandons their device, affirming that search warrants remain relevant in the digital age. Our constitutional rights must continue to apply in our digital lives, regardless of the fate of our devices.

Referrer: MiMub in Spanish